I’m visiting Weihai this weekend because a beach vacation doesn’t really count unless it’s 30 degrees* outside with a stiff sea breeze.

Weihai is a charmless—but very clean—city set on a historic harbor. Most of the older structures (including whole villages once constructed using sea weed) have long since been plowed under. In their place are rows of copy-cat ‘business’ hotels, bath resorts, and shopping malls. If the builders of the Mall of America in Minnesota had chosen to build their monument to American consumerism by leveling Mystic, CT it might look like Weihai.

Weihai is also the where the Japanese Imperial Navy and the Beiyang Fleet of the Qing Empire fought the decisive battle of the Sino-Japanese War.

The flagship of the Beiyang fleet was the Dingyuan 定远. She was an armored warship commissioned by the Qing imperial government and built in Germany in 1881. The Dingyuan was over 300 feet long and with a hull nearly a foot thick around the waterline and carried four 305-mm and two 150-mm guns manufactured by Krupp as well as six 37-mm guns and three torpedo tubes. The 305-mm and 150-mm guns were mounted in turrets, with the smaller guns placed fore and aft. The big 305-mm boomers, each with a range of over 6 miles**, were set just forward of amidships, the port side 305-mm gun placed just a bit forward from its counterpart on the starboard side.

All in all, she was an impressive ship with one catastrophic design flaw. I’ll give you a hint: It had to do with the gun placements.

In her day she was as imposing as any ship in the Western Pacific. Even after she had been declared sea worthy and ready for delivery, the French asked the British not to allow the Dingyuan or her sister ship (the Zhenyuan) through the Suez Canal. The French were fighting a war agains the Qing and felt that the new ships might tip the balance of power in the South China Sea. The French won that war and the Dingyuan had to wait two years before finally arriving into service on the China coast.

A decade later, when the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1894, it was the Dingyuan led the charge against the Japanese fleet, but despite the firepower provided by the Dingyuan and the Zhenyuan, the war proved disastrous for the Qing Empire.

At the Battle of the Yalu River, an early tactical error put the Beiyang Fleet on its heels. The commander of the fleet, Ding Ruchang, originally lined his ships up in a row, with the Dingyuanand Zhengyuan at the center. When the Japanese tried to outflank the Beiyang fleet, Admiral Ding realized the center battleships couldn’t fire their main guns on the Japanese ships without hitting the smaller Beiyang ships on the left and right.

Admiral Ding then ordered the captain of the Ding Yuan, Liu Buchuan, to change the course. The maneuver would have given the battleship an open shot at the Japanese ships but would have exposed the Dingyuan to enemy fire.

What happened next is not entirely clear.

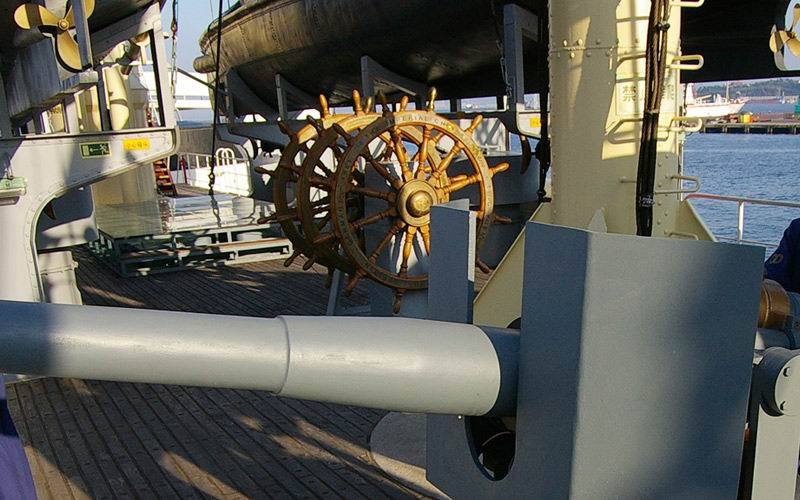

Port turret guns on the Dingyuan

Some say the captain refused to obey the order to bring the Dingyuan about and instead ordered the main 305-mm guns to fire forward. It was well known since the earliest sea trials that the Dingyuan suffered a major design flaw: the main 305-mm guns were mounted on the side of the ship. Bringing those guns to bear directly forward meant they would be firing directly at the support beams of the flying bridge…where Admiral Ding stood commanding the fleet. The guns fired and the flying bridge collapsed. Several officers died instantly. Admiral Ding was trapped under the wreckage, his legs crushed by a large piece of twisted metal.

Other accounts say that Liu was ordered to fire the main guns to give cover for the smaller vessels. The collapse of the flying bridge was an unfortunate error and not the deliberate act of a cowardly officer trying to protect his ship (and skin) from an overzealous admiral. In this version, Captain Liu, as the only senior officer not incapacitated in the accident, bravely took command of the fleet thereby preventing (well, postponing) its total annihilation.

Whatever happened, with the flagship disabled the Beiyang fleet was at the mercy of the Japanese Imperial Navy. The remaining Beiyang ships limped back to the Port of Lushun before they retreated further to the relative safety of the harbor at Weihai.

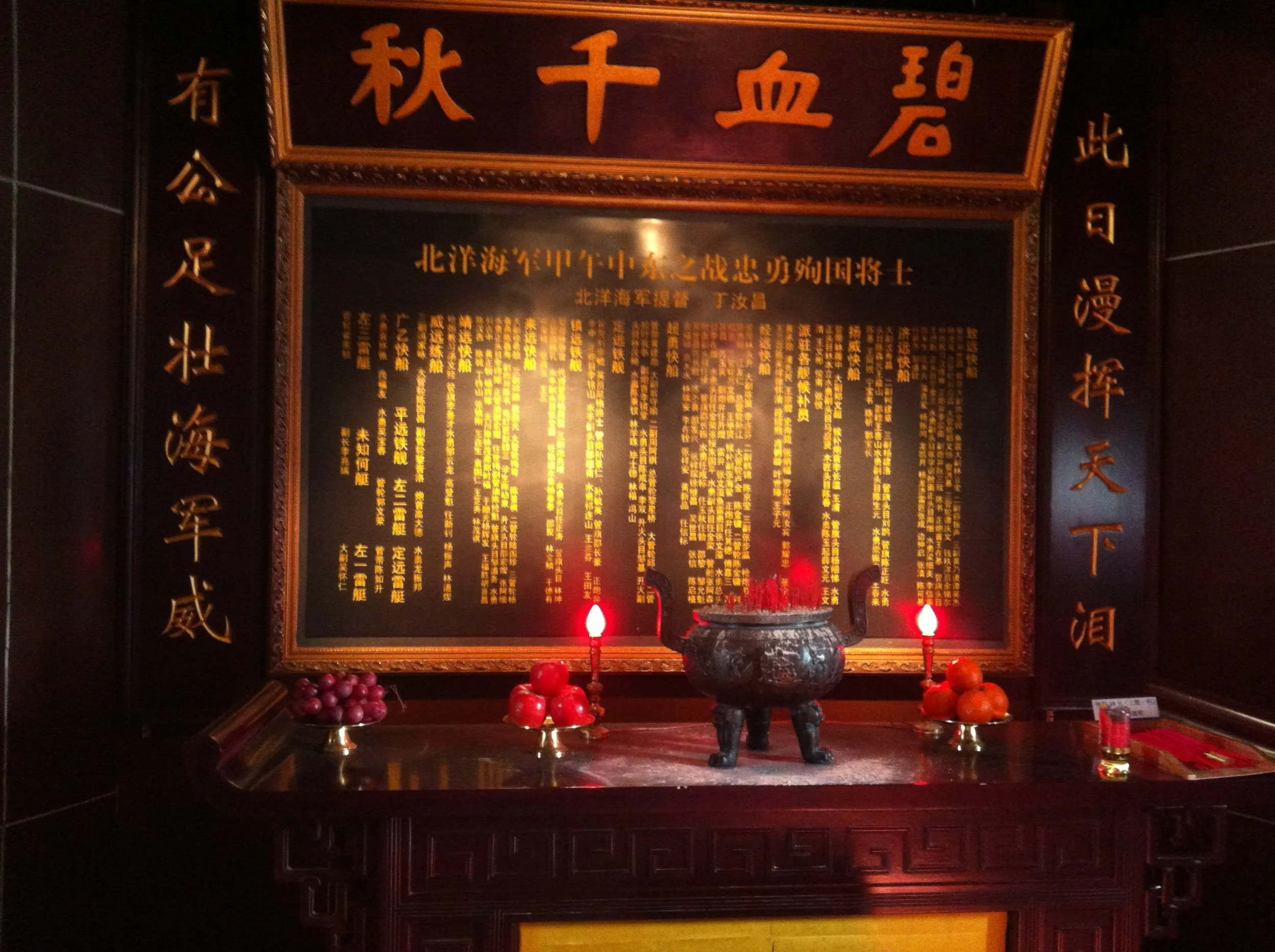

Shrine onboard the replica of the Dingyuan.

120 years ago this month, the Imperial Japanese Navy pursued the remains of the Qing Beiyang Fleet to Weihai. Rather than test the harbor defenses, the Japanese landed troops, marched them overland, and seized control of the guns defending the harbor. The Japanese soldiers then used the Chinese guns to fire on the Chinese ships. The result was the complete annihilation of the Beiyang Fleet.

During the battle, the Dingyuan suffered catastrophic damage from both the shore guns and Japanese torpedoes. Rather than see his ship fall into Japanese hands, Captain Liu ordered the Dingyuan scuttled. China’s early dreams of being a naval power sank to the bottom of the Weihai Harbor.

Later that evening both Captain Liu and Admiral Ding committed suicide by opium overdose.

The remains of the actual Dingyuan have never been recovered although parts of the ship (the bell, Captain Liu’s desk) were taken as souvenirs to Japan. Today an exact replica of the ship is open to visitors on the waterfront in Weihai. On board, there’s a museum to Chinese naval history, along with recreations of the ship’s quarters, officer’s mess, hospital, fire room, and the brig. Those interested in naval history, or Chinese history, will find her an interesting way to spend a few hours, provided they can ignore the heavy patina of anti-Japanese propaganda.

Dingyuan (Ting Yuen) Warship Tourist Area. Posted admission is 75 RMB but we got in today (off-season) for 30 RMB per person. Admission includes a guided tour in Chinese. Address: 山东威海海滨北路9号,海港大厦南首 (Weihai waterfront, located near the Haigang Dasha on Haibin Bei Lu) Telephone: 0631-5280718